A Systems Perspective on Motor Control, Part One

Dynamic systems theory (DST) is gaining influence in the world of movement rehab and performance as way to explain how motor learning is optimized. The basic premise is that movement behavior is the result of complex interactions between many different subsystems in the body, the task at hand, and the environment. Given this complexity, systems theory is an appropriate tool to analyze how movement behaviors change and how learning occurs.

In this post and a follow-up, I will review some basic concepts from DST, and how you can use them with clients. After reading this, you might conclude that DST helps explain some of the practices and intuitions of some great movement coaches.

(By the way, if you want more background on some of the concepts in this post, and how they apply in the context of pain, you might be interested in this post on A Systems Perspective on Chronic Pain.)

Consider the intelligent behavior of a colony of insects, such as a beehive. There isn’t any one bee that knows how to do all the important things that need to be done: build a hive; make honey; raise babies; repel predators, etc. Instead, these jobs just get done as a result of the complex interactions between thousands of different bees, who are all just mindlessly following simple algorithms for behavior. Similarly, the intelligence controlling our movement emerges from complex interactions between millions of different body parts and the environment.

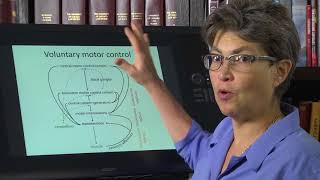

But what about the central nervous system? Isn’t it the central controller of the body? In some sense yes – the CNS issues all the commands that cause muscles to fire in meaningful patterns. But the CNS is itself a complex system composed of many parts. And its behavior depends on its interaction with many other systems in the body, like the immune system, endocrine system, musculoskeletal system, and the environment.

This is why DST deemphasizes the role of “top-down” determinants of movement like the CNS, or “motor programs”, and focuses more attention on “bottom-up” factors like the structure of the body, the environment, and the nature of the task at hand.

For an example of how much these factors matter for coordinated movement, check out this video of a robot walking without any onboard computers or even motors. The intelligence that controls the robot is built into its structure. When that structure is put in the right context, it just does its thing:

Complex systems, self –organization and top-down control

The major premise of DST is that the body is a complex system composed of millions of interacting parts. The intelligence that coordinates the body is not localized in any one particular part, but emerges from the complex interactions of all the different parts. Thus, unlike a simple machine such as a thermostat, complex systems exhibit behavior that is controlled without a central controller.

To describe this seeming paradox, DST uses terms like self-organization, emergence, and multi-causality. These terms sound pretty exotic, but there’s no magic involved. Self-organization doesn’t imply some sort of vital life energy that defies the laws of physics. But how can you have control without a controller?

This robot didn't need to learn to walk, it just needed the right kind of environment (a sloped ground) and a little push from his Daddy. Are babies any different? Some interesting studies by Esther Thelen showed something similar about what gets babies walking.

Информация по комментариям в разработке