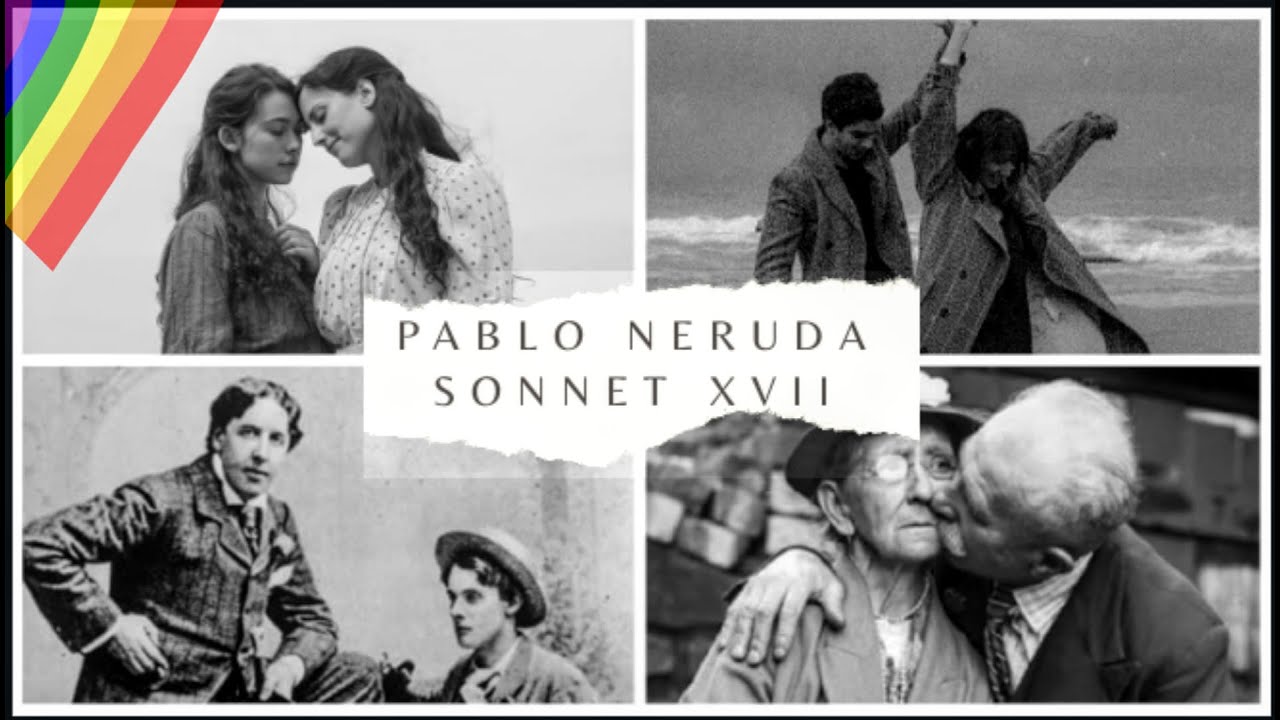

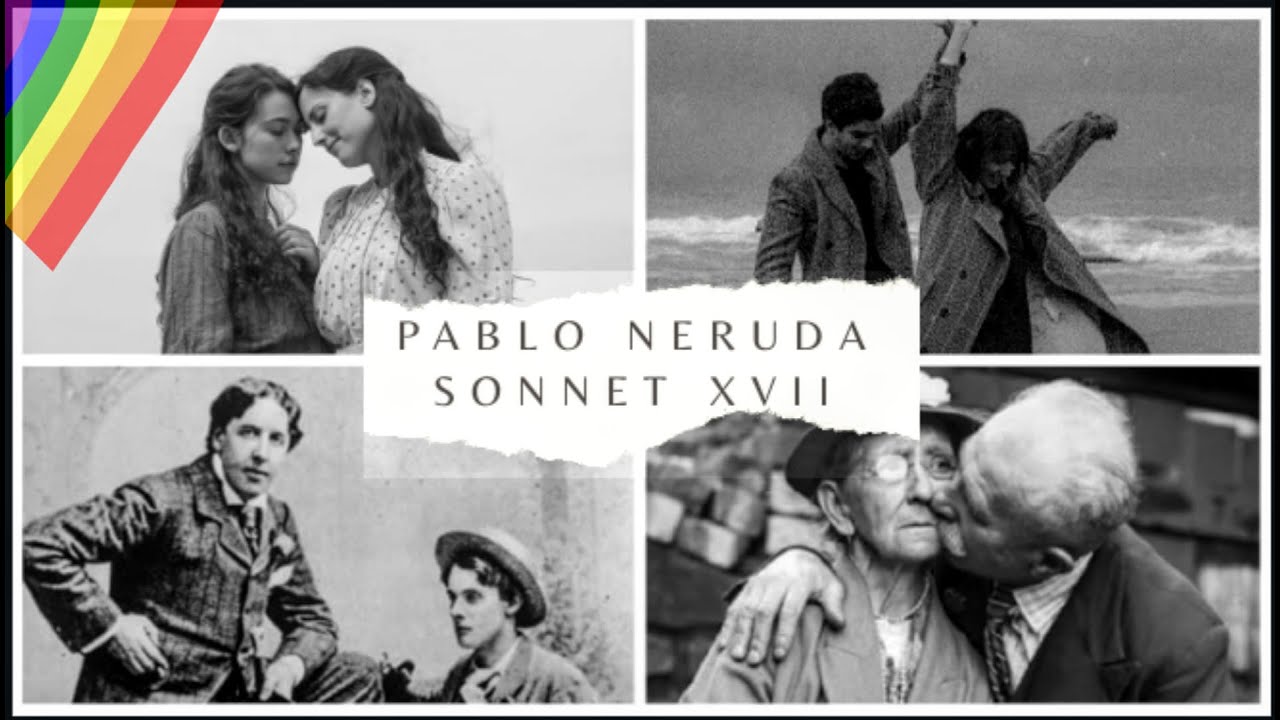

This sonnet was written by Neruda to his wife but I dedicate this particular sonnet celebrating love in different forms and faces, celebrating the differences. #pridemonth #lgbtcommunity

#Sonnet17

I do not love you as if you were salt-rose, or topaz,

or the arrow of carnations the fire shoots off.

I love you as certain dark things are to be loved,

in secret, between the shadow and the soul.

I love you as the plant that never blooms

but carries in itself the light of hidden flowers;

thanks to your love a certain solid fragrance,

risen from the earth, lives darkly in my body.

I love you without knowing how, or when, or from where.

I love you straightforwardly, without complexities or pride;

so I love you because I know no other way than this:

where I, does not exist, nor you,

so close that your hand on my chest is my hand,

so close that your eyes close as I fall asleep.

Music:

http://youtu.be/www.youtube.com/johne...

No copyright infringement intended with the images used. It belongs to the rightful owner

Biography from www.poetryfoundation.org--

#PabloNeruda is one of the most influential and widely read 20th-century poets of the Americas. “No writer of world renown is perhaps so little known to North Americans as Chilean poet Pablo Neruda,” observed New York Times Book Review critic Selden Rodman. Numerous critics have praised Neruda as the greatest poet writing in the Spanish language during his lifetime. John Leonard in the New York Times declared that Neruda “was, I think, one of the great ones, a Whitman of the South.” Among contemporary readers in the United States, he is largely remembered for his odes and love poems.

Born Ricardo Eliezer Neftali Reyes y Basoalto, Neruda adopted the pseudonym under which he would become famous while still in his early teens. He grew up in Temuco in the backwoods of southern Chile. Neruda’s literary development received assistance from unexpected sources. Among his teachers “was the poet Gabriela Mistral who would be a Nobel laureate years before Neruda,” reported Manuel Duran and Margery Safir in Earth Tones: The Poetry of Pablo Neruda. “It is almost inconceivable that two such gifted poets should find each other in such an unlikely spot. Mistral recognized the young Neftali’s talent and encouraged it by giving the boy books and the support he lacked at home.”

Neruda’s politics had an important impact on his poetry. Clayton Eshleman wrote in the introduction to Cesar Vallejo’s Poemas humanos/ Human Poems that “Neruda found in the third book of Residencia the key to becoming the 20th-century South American poet: the revolutionary stance which always changes with the tides of time.” Gordon Brotherton, in Latin American Poetry: Origins and Presence, expanded on this idea by noting that “Neruda, so prolific, can be lax, a ‘great bad poet’ (to use the phrase Juan Ramon Jimenez used to revenge himself on Neruda). And his change of stance ‘with the tides of time’ may not always be perfectly effected. But … his dramatic and rhetorical skills, better his ability to speak out of his circumstances, … was consummate. In his best poetry (of which there is much) he speaks on a scale and with an agility unrivaled in Latin America.”

“.”

According to Neruda, “It was through metaphor, not rational analysis and argument, that the mysteries of the world could be revealed,” remarked Stephen Dobyns in the Washington Post. However, Dobyns noted that Passions and Impressions “shows Neruda both at his most metaphorical and his most rational. … What one comes to realize from these prose pieces is how conscious and astute were Neruda’s esthetic choices. In retrospect at least his rejection of the path of the maestro, the critic, the rationalist was carefully calculated.” In his speech upon receiving the Nobel Prize, Neruda noted that “there arises an insight which the poet must learn through other people. There is no insurmountable solitude. All paths lead to the same goal: to convey to others what we are.”

In 2003, 30 years after Neruda’s death, an anthology of 600 of Neruda’s poems arranged chronologically was published as The Poetry of Pablo Neruda. The collection draws from 36 different translators, and some of his major works are also presented in their original Spanish. Writing in the New Leader, Phoebe Pettingell pointed out that, although some works were left out because of the difficulty in presenting them properly in English, “an overwhelming body of Neruda’s output is here … and the collection certainly presents a remarkable array of subjects and styles.” Reflecting on the life and work of Neruda in the New Yorker.

Информация по комментариям в разработке