In this IIMR webinar, Professor Steve Hanke discusses alternative monetary regimes to fight inflation in emerging economies.

SUMMARY OF THE TALK

There are three main types of exchange rate systems: floating, fixed and pegged.

A) Floating. There is no exchange rate commitment but an independent monetary policy. The source of the monetary base is domestic.

B) Fixed exchange rate, being the opposite of (A): There is an exchange rate policy, but no independent monetary policy. All origins of change in the monetary base is foreign.

C) Pegged. This is the most common arrangement in emerging markets. There is an exchange rate policy and monetary policy. Domestic and foreign sources make the monetary base, and there are conflicts, and there are often balance of payment crises, and exchange controls. "These are nothing but trouble", according to Prof. Hanke.

Re: B) Fixed rate system. Two ways to do this:

1) Via 'dollarization', i.e. to get rid of the local currency and replace it with some other currency, which is called, generically, 'dollarization', but does not have to be based on the (US) Dollar, but can be any currency. There are about 33 countries in the world that are 'dollarized'.

2) Via a currency board. With a currency board, one has a fixed exchange rate, which is fixed to an anchor currency, there are no further exchange controls, so the local currency becomes a clone of whatever the anchor is.

Historically, there have been about 70 currency board exchange rate systems, none of which have ever failed. Today, there are only about 15 of them. So if these systems work so well and there has never been a failure, why are there so few now? (1) Several currency boards were colonial: eg. local currencies pegged to the British Pound -- this was abolished in the decades after WW II with the demise of the colonial empires. (2) Keynesian economics has gained in popularity, which means interventionist economic policy, and one needs an active central bank and a domestic monetary policy to fine-tune the economy -- whereas a currency board has no room for that. (3) The Bretton-Woods system of 1944 created the IMF and the World Bank, and these institutions need central banks, which can be at odds with a currency board system.

Some think that currency boards are not in line with free markets, but they are mistaken. Keynes' case for floating exchange rates was targeted to the countries participating in the Bretton Woods sytem; not in general.

Loopholes in the Currency Board system can be (i) if the central bank holds less than 100% reserve cover in the foreign currency, (ii) if the reserves are local bonds denominated in the anchor currency, and (iii) if a huge amount of discretion is allowed in the currency system, leading to too much fluctuations in net domestic assets, which can lead to reckless sterilisation.

Questions addressed in this talk are:

For a country with a record of persistent and high inflation, would a currency board or the full dollarization of the economy be preferable to monetary competition?

So, it would be a currency board along with no preference for any currency, which just would have no legal tender status -- correct?

Is a currency board vulnerable to inflation in the reserve country, for example in Hong Kong, at the risk of importing current US inflation?

The US federal reserve has been inflating domestic and international markets with a huge amount of dollars in the recent years. How could this affect the dominant position of the dollar, as the world's reserve currency?

Suppose the government of a country has decided to implement a currency board, does the government earn any seignorage at all under such a regime?

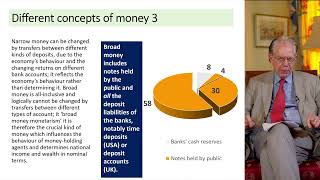

What do you believe accounts for the wide-spread neglect of the quantity of money by much of the economics profession today?

According to your experience, does monetary indiscipline work hand in hand with budgetary imbalances?

Most countries in the Middle East adopt a currency board system with a fixed exchange rate with the US dollar as an anchor. Yet economic instability is rampant. The most recent example is Lebanon. Would this suggest the currency board is not such a good arrangement after all?

Under what conditions would a central bank with no exchange rate policy be preferable to a currency board?

In a pegged rate system, how would you measure the degree of sterilization engaged in by a central bank every now and then?

Why do you believe that divisia money is are not commonly used by monetary economists, even those who find broad monetary aggregates important?

ABOUT THE IIMR

The Institute for International Monetary Research (IIMR) provides analysis and insight into trends in money and banking, and their impact on the world's leading economies. Its purpose is to demonstrate and publicise the strong relationship between the quantity of money on the one hand, and the levels of national income and expenditure on the other.

Website: https://mv-pt.org

Информация по комментариям в разработке