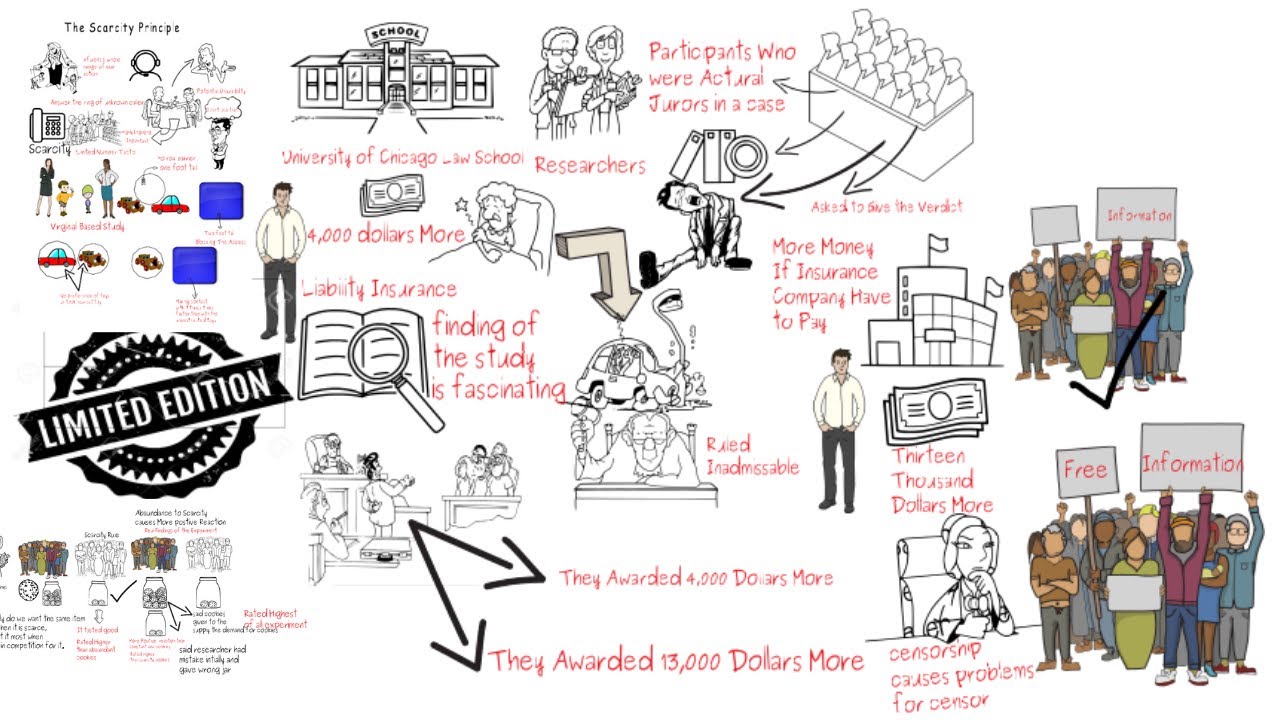

The Scarcity principle:

Scarcity's influence over a whole range of Our actions. For instance, We routinely will interrupt an interesting face-to-face conversation to answer the ring of an unknown caller. In such a situation, the caller has a compelling feature that my face-to-face partner does not: potential unavailability.

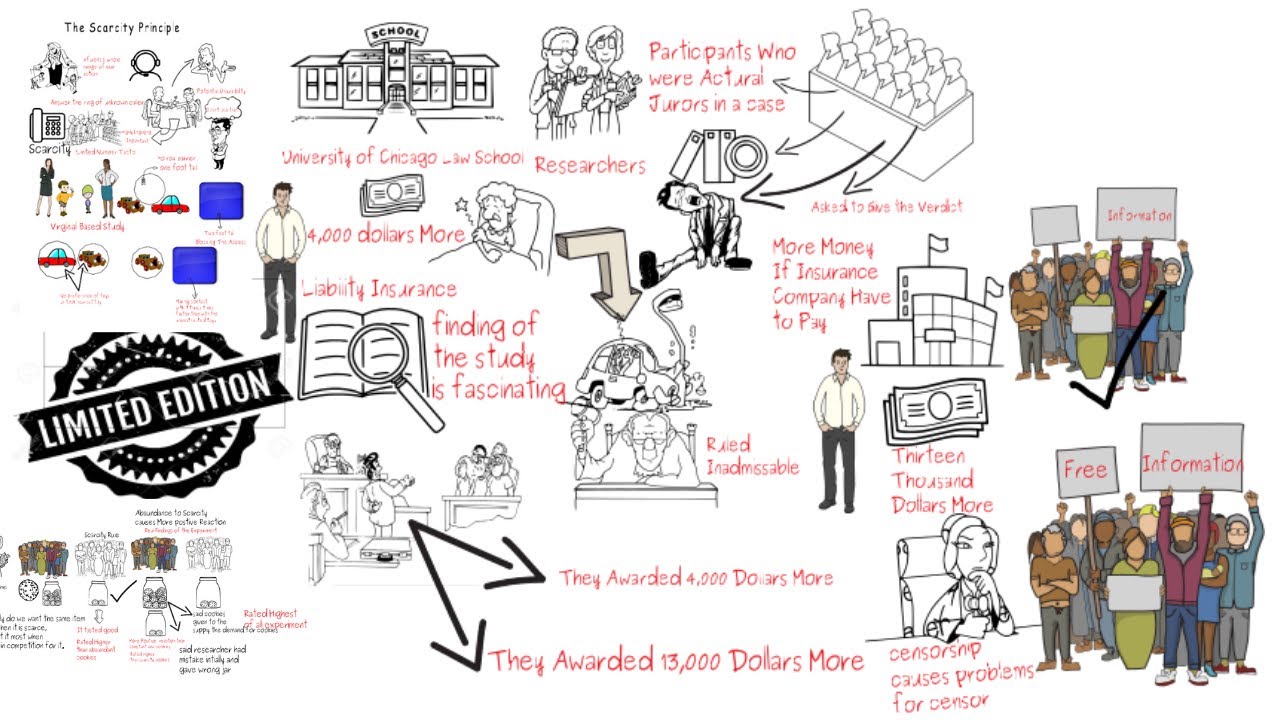

There is another study conducted by the University of Chicago Law School. One reason

the results of the Chicago jury project are informative is that the participants were individuals who were actually on jury duty at the time and who agreed to be members of “experimental juries” formed by the researchers.

These experimental juries then heard tapes of evidence from previous trials and deliberated as if they were deciding the case.

In the study most relevant to our interest in official censorship, thirty such juries heard the case of a woman who was injured by a car driven

by a careless male defendant.

The first finding of the study was no surprise:

When the driver said he had liability insurance, the jurors awarded his victim an average of four thousand dollars more than when he said he had no insurance .

Thus, as insurance companies have long suspected, juries make larger awards to victims if an insurance company will have to pay.

The second finding of the study is the fascinating one,though. If the driver said he was insured and the judge ruled that evidence inadmissible , the instruction to disregard had a boomerang effect, causing an average award of thirteen thousand rupees. So when certain juries learned that the driver was insured, they increased the damage payment by four thousand dollars. But when other juries were told officially that they must not use that information, they used it still more, increasing the damage payment by

thirteen thousand dollars. It appears, then, that even proper, official censorship in a courtroom setting creates problems for the censor.

We react to information restriction there, as usual, by valuing the banned information more than ever. The scarcity principle

is more effective at some times than at other times. An important practical problem, then, is to find out when scarcity works best on us.

An experiment devised by social psychologist Stephen Worchel. The basic procedure used by Worchel was simple: Participants in a consumer preference study were given a chocolate-chip cookie from a jar and asked to taste and rate its quality. For half of the raters, the jar contained

ten cookies; for the other half, it contained just two. As we might expect from the scarcity principle, when the cookie was one of the only two available, it was rated more favorably than when it was one of ten. The cookie in short supply was rated as more desirable to eat in the future, more attractive as a consumer item, and more costly than the identical cookie in abundant supply.

The real worth of the cookie study comes from two additional findings.

The first of these noteworthy results involved a small variation in the experiment’s basic procedure. Rather than rating the cookies under conditions of constant scarcity, some participants were first given a jar of ten cookies that was then replaced by a jar of two cookies. Thus, before taking a bite, certain of the participants saw their abundant supply of cookies reduced to a scarce supply. Other participants, however, knew only scarcity of supply from the outset, since the number of cookies in their jars was left at two. In the cookie experiment, the answer was plain. The drop from abundance to scarcity produced a decidedly more positive reaction to the cookies than did constant scarcity.

We’ve already seen from the results of that study that scarce cookies were rated higher than abundant cookies and that newly scarce cookies were rated higher still. Remember that in the experiment the participants who experienced new scarcity had been given a jar of ten cookies that was then replaced with a jar of only two cookies. Actually, the researchers did this in one of two ways. To certain participants, it was explained that some of their cookies had to be given away to other raters to supply the demand for cookies in the study.

To another set of participants, it was explained that their number of cookies had to be reduced because the researcher had simply made a mistake and given them the wrong jar initially. The results showed that those whose cookies became scarce through the process of social demand liked them significantly more than those whose cookies became scarce by mistake. In fact, the cookies made less available through social demand were rated the most desirable of any in the study. This finding highlights the importance of competition in the pursuit of limited resources. Not only do we want the same item more when it is scarce, we want it most when we are in competition for it.

Информация по комментариям в разработке