Female German POWs' Voices Life in US Camps After Capture

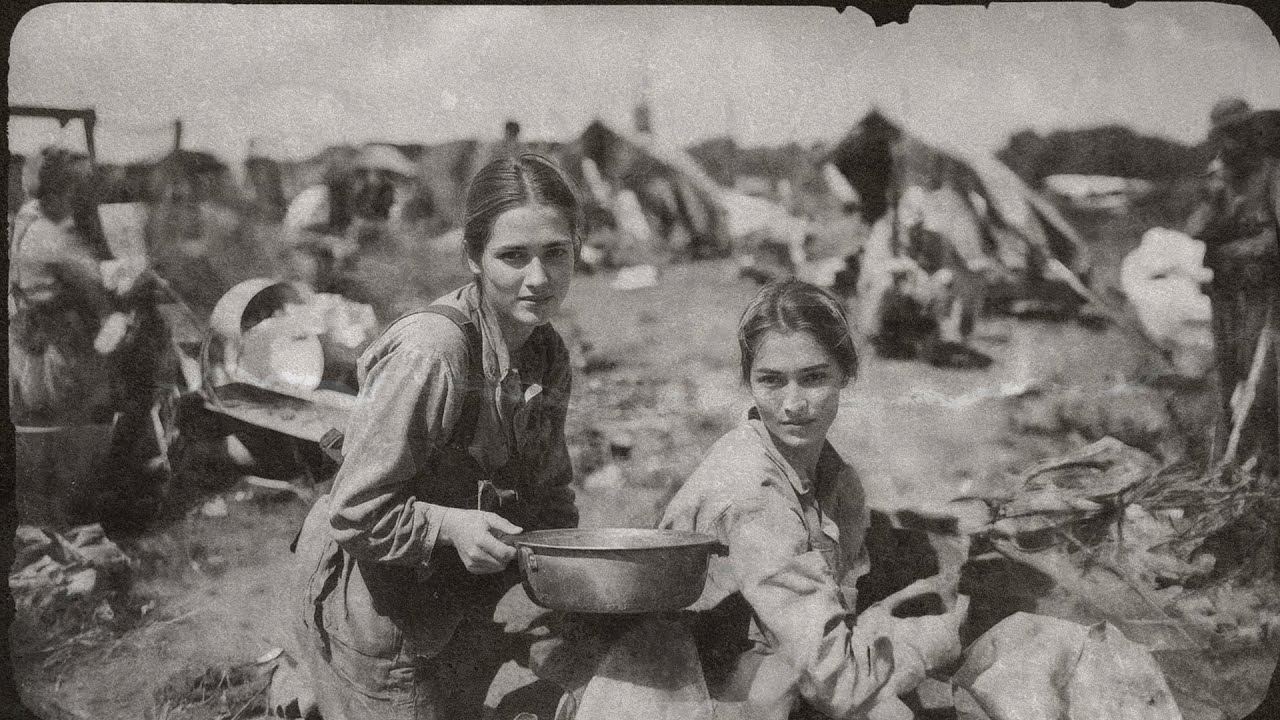

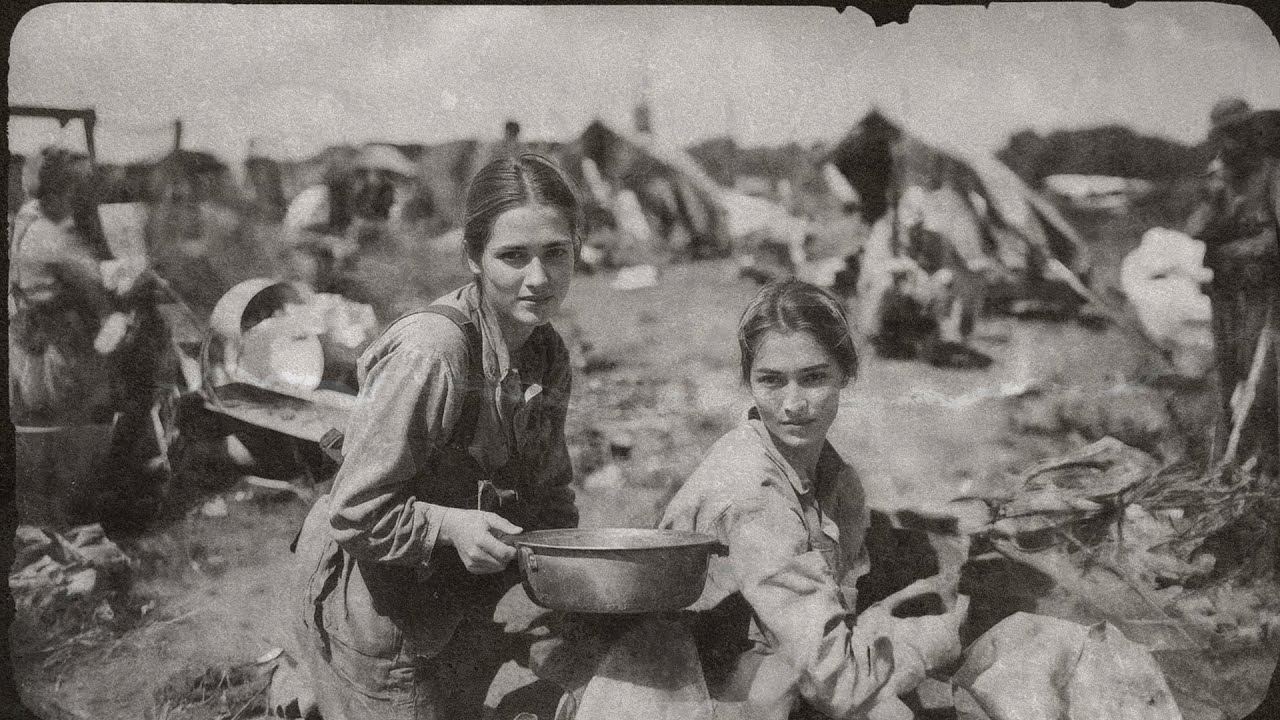

March 14th, 1945. 1620 hours. Camp Concordia, Kansas. The dust from the transport trucks hadn't yet settled when Captain Robert Henneman of the US Army Military Police Corps realized that everything he thought he knew about prisoner processing was about to be challenged. Through the chain-link fence, he watched as seventy-three women in tattered Wehrmacht auxiliary uniforms stepped down from the canvas-covered vehicles, their faces blank with exhaustion and something else he couldn't quite name.

Fear, certainly. But also a strange defiance that seemed to say they had already survived the worst and whatever came next was just epilogue. In his clipboard, the manifest read simply: German Female Personnel, Captured Remagen Bridge Sector, Non-Combatant Status Pending Review. What it didn't say was that these women would force the United States Army to confront questions it had never anticipated asking. How do you imprison women in a system designed entirely for men?

How do you maintain military discipline while preserving basic dignity? And most troubling for Robert, how do you remain professionally detached when the enemy stops looking like the enemy and starts looking like someone's sister, someone's daughter, someone's wife? Before we jump back in, tell us where you're tuning in from, and if this story touches you, make sure you're subscribed because tomorrow, I've saved something extra special for you! Robert had arrived at Camp Concordia six weeks earlier, reassigned from the European Theater after taking shrapnel in his left shoulder during the crossing of the Rhine. The wound had healed cleanly, but Army Medical Services deemed him unfit for frontline duty.

At thirty-two, with eight years of military police experience and a law degree from Columbia gathering dust in a trunk somewhere in New Jersey, he was overqualified for guard duty at a prisoner of war camp in the Kansas wheat fields. Yet here he stood, watching history arrive in the back of Army trucks, wondering if the war had followed him home after all. Camp Concordia had been operating since 1943, housing primarily German soldiers captured in North Africa and later in the Italian campaign. At its peak, the facility held over four thousand prisoners across multiple compounds, all male, all processed according to established Geneva Convention protocols that had been refined over two years of operation. The camp had achieved a reputation for efficiency and, remarkably, for maintaining positive relations between captors and captives.

German prisoners worked on local farms, supplementing the labor shortage caused by American men serving overseas. Some had even formed friendships with Kansas farmers, learning English, sharing meals, playing chess on Sunday afternoons. But women prisoners were an entirely different matter. The United States had captured relatively few German women during the war, and those who were taken were usually quickly processed and released or transferred to British custody in Europe. The seventy-three women arriving at Concordia represented the largest group of female German prisoners ever brought to American soil, and nobody in the chain of command seemed quite sure what to do with them.

The women had been captured during the chaotic final weeks of the Battle of Remagen, when American forces secured the Ludendorff Bridge and poured across the Rhine into the German heartland. Most had served as Nachrichtenhelferinnen, communications auxiliaries for the Wehrmacht, operating telephone switchboards and radio equipment in underground command bunkers. Others had been Luftwaffenhelferinnen, working in air defense operations, plotting aircraft movements and coordinating flak batteries. A few had served in administrative roles, managing supply records and personnel files. Under Nazi Germany's total war doctrine, hundreds of thousands of women had been mobilized into auxiliary military services, wearing uniforms, living in barracks, and working in roles that freed men for combat duty.

They were not soldiers in the traditional sense, they did not carry weapons or receive combat training, but they were undeniably part of the military apparatus. The legal question of their status had been debated in Washington for months. Were they prisoners of war entitled to Geneva Convention protections? Were they civilian internees subject to different regulations? The paperwork arriving with them suggested that nobody had reached a definitive conclusion.

Colonel Richard Hartwick, the camp commander, had called an emergency meeting of senior staff the day before the women's arrival.

#germanpows #WomenInWWII #wwiistories #prisonerofwar #powexperiences #wwiihistory #historyshock #wwiiheroes #warstories #historicevents #UntoldWWIIStories #wwiiexperience #powlife #femalevoicestatus #humanityinwar #WWIILessons #wwiiwomen #historicalstoriesinurdu

Информация по комментариям в разработке