The Roman Jewish War | The conflict that changed the World

The Roman period (63 BCE–135 CE)

Rome and Jerusalem: The Clash of Ancient Civilizations

A magisterial history of the titanic struggle between the Roman and Jewish worlds that led to the destruction of Jerusalem.

Martin Goodman—equally renowned in Jewish and in Roman studies—examines this conflict, its causes, and its consequences with unprecedented authority and thoroughness. He delineates the incompatibility between the cultural, political, and religious beliefs and practices of the two peoples and explains how Rome's interests were served by a policy of brutality against the Jews. At the same time, Christians began to distance themselves from their origins, becoming increasingly hostile toward Jews as Christian influence spread within the empire. This is the authoritative work of how these two great civilizations collided and how the reverberations are felt to this day.

The Roman period (63 BCE–135 CE)

New parties and sects

Palestine during the time of Herod the Great and his sons.

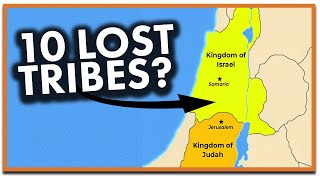

Under Roman rule a number of new groups, largely political, emerged in Palestine. Their common aim was to seek an independent Jewish state. They were also zealous for, and strict in their observance of, the Torah.

After the death of King Herod, a political group known as the Herodians, who apparently regarded Herod as the messiah, sought to reestablish the rule of Herod’s descendants over an independent Palestine as a prerequisite for Jewish preservation. Unlike the Zealots, however, they did not refuse to pay taxes to the Romans.

The Zealots, whose appearance was traditionally dated to 6 CE, were one of five groups that emerged at the outset of the first Jewish war against Rome (66–73 CE), which began when the Jews expelled the Romans from Jerusalem, the client king Agrippa II fled the city, and a revolutionary government was established. The Zealots were a mixture of bandits, insurgents from Jerusalem, and priests, who advocated egalitarianism and independence from Rome. In 68 they overthrew the government established by the original leaders of the revolt and took control of the Temple during the civil war that followed; many of them perished in the sack of Jerusalem by the Roman general (and later emperor) Titus (reigned 79–81) or in fighting after the city’s fall. The Sicarii (Assassins), so-called because of the daggers (sica) they carried, arose about 54 CE, according to Josephus, as a group of bandits who kidnapped or murdered those who had found a modus vivendi with the Romans. It was they who made a stand at the fortress of Masada, near the Dead Sea, committing suicide rather than allowing themselves to be captured by the Romans (73).

Josephus tells us in Antiquities, book 14 chapter 4, that after taking Jerusalem, Pompey entered the Holy of Holies:

For Pompey went into [the inaccessible parts of the Temple], and not a few of those that were with him also; and saw all that which it was unlawful for any other men to see, but only for the High Priests. There were in that temple the golden table; the holy candlestick; and the pouring vessels; and a great quantity of spices: and besides these there were among the treasures, two thousand talents of sacred money. Yet did Pompey touch nothing of all this; on account of his regard to religion; and in this point also he acted in a manner that was worthy of his virtue. The next day he gave order to those that had the charge of the temple to cleanse it, and to bring what offerings the law required to God, and restored the High Priesthood to Hyrcanus

63 BC

Catapults kept up a continuous pressure by hurling heavy stones; a battering ram broke the wall, and Pompey's soldiers entered the Temple terrace, where they started to kill the defenders. Many Jewish soldiers committed suicide, because they did want to see the profanation of the sanctuary (June/July 63).

Siege of Jerusalem (63 BC)

A number of other parties—various types of Essenes, Damascus covenanters, and the Qumrān–Dead Sea groups—were distinguished by their pursuit of an ascetic monastic life, disdain for material goods and sensual gratification, sharing of material possessions, concern for eschatology, strong apocalyptic views in anticipation of the coming of the messiah, practice of ablutions to attain greater sexual and ritual purity, prayer, contemplation, and study. The Essenes differed from the Therapeutae, a Jewish religious group that had flourished in Egypt two centuries earlier, in that the latter actively sought “wisdom” whereas the former were anti-intellectual. Only some of the Essenes were celibate. The Essenes have been termed “gnosticizing Pharisees” because of their belief, shared with the gnostics, that the world of matter is evil.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Juda...

Информация по комментариям в разработке