*Freehand Milling: When the Chainsaw Becomes a Sawmill*

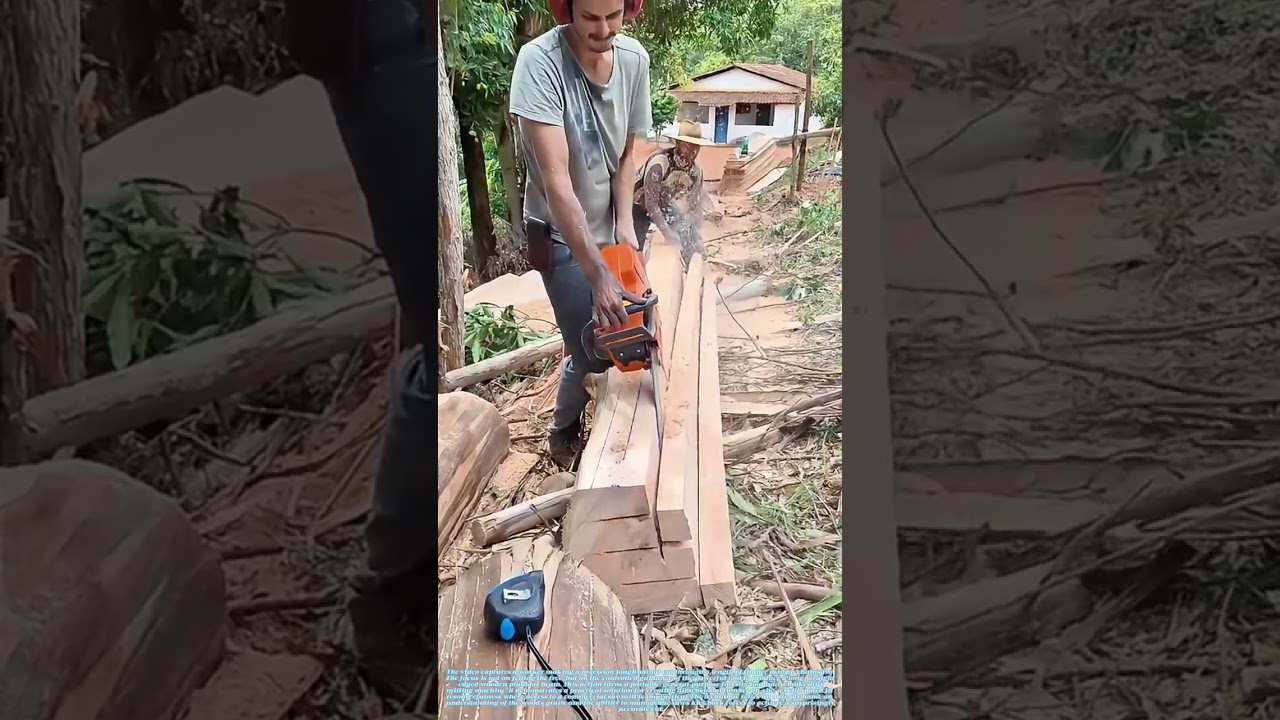

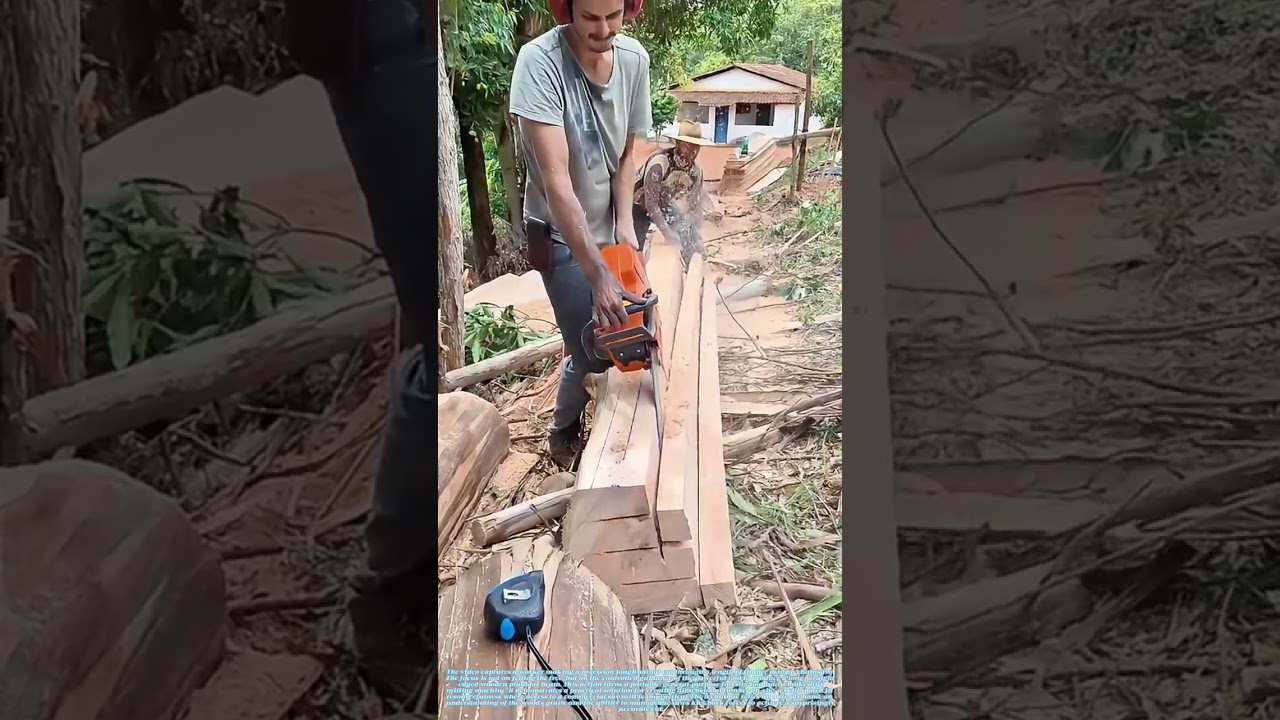

In the absence of a stationary sawmill, the chainsaw—a tool synonymous with raw cutting power—is adapted for a task requiring linear precision. This practice, common among remote builders, homesteaders, and skilled woodsmen, is an exercise in translating force into finesse. It involves using the chainsaw's aggressive cutting chain to follow a straight line along a log's length, effectively "slabbing" or "ripping" it into usable boards or beams. The goal is to minimize waste and maximize utility from a single piece of timber, relying entirely on the operator's skill to guide the cut.

• *From Crosscut to Rip Cut:* A chainsaw is primarily designed for crosscutting—sawing across the wood grain. Ripping, or cutting with the grain, presents a different challenge. The chain's teeth are optimized for severing wood fibers laterally, not for peeling them apart lengthwise. A standard chain can still perform the rip cut, but it requires more careful handling and produces a different, often rougher, chip texture.

• *The Importance of the Guide:* Precision is achieved through the use of a physical guide. An experienced operator may use a long, straight piece of lumber or a factory-made guide rail clamped onto the log. This simple jig provides a fixed reference surface for the chainsaw's body or guide bar, ensuring the cut follows a true line from one end of the log to the other.

• *Managing Physics and Forces:* Ripping with a chainsaw requires constant management of the tool's forces. The saw wants to follow the path of least resistance, which can lead to "wandering" if the grain changes direction. The operator must apply steady, forward pressure while simultaneously controlling side-to-side movement and being acutely aware of the potential for kickback, especially at the cut's beginning and end.

• *The Two-Cut Method for Beams:* To produce a large, squared beam from a round log, a common technique involves making two perpendicular rip cuts. First, a flat face is created by removing a slab from one side of the log. The log is then rolled so this flat side rests stably on the ground or on supports. A second vertical rip cut is made down to the desired width, resulting in a perfectly square corner. This process is repeated for all four sides.

• *Practicality Over Perfection:* The resulting lumber is rarely as dimensionally perfect or smooth as mill-sawn wood. It retains the character of the chainsaw's cut—visible kerf marks and a textured surface. This is often an acceptable trade-off for on-site construction of sheds, fencing, rustic furniture, or other projects where commercial lumber is unavailable or cost-prohibitive to transport.

• *A Skill of Resource Scarcity:* This method flourished in frontier and remote rural settings and remains a valuable skill in areas with abundant timber but limited infrastructure. It embodies the principle of "use what you have" to create what you need, turning a single tool into a mobile workshop.

• *Safety as the Foremost Consideration:* The process is inherently more hazardous than using a table saw or band saw. It demands rigorous safety protocols: secure log stabilization, appropriate personal protective equipment (chaps, helmet, eye and ear protection), a sharp chain to reduce binding, and a deep respect for the tool's power.

In the roar of the engine and the stream of coarse sawdust, there is a quiet assertion of human agency over material. It is a demonstration that precision is not solely the domain of calibrated machines, but can be an extension of practiced skill—a deliberate line drawn through nature's grain with the most elemental of powered tools, converting potential into practical form where it stands.

Информация по комментариям в разработке