When you mention Beethoven's Piano Concerti, there are few people, musicians or not, experts or not, who won't find anything personal to say about them - there's just something about the Five that seems to make them connect with the listener in a personal way.

There's the first and second, both delicate, bold, and great amounts of fun - while definitely at least somewhat detaching themselves quite a bit from Mozart's style, no matter what they'll say. The third, confident and impartial, like a family father. The fourth, somehow both delicate and grandiose, raw and guttural by its improvisatory nature - the most human of all piano concertos, really. And the fifth - sensitive, but never entirely departing from its belligerent roots, touching at times with exaltation.

And that's it - that's all the five. Yet unbeknownst to most, Beethoven didn't write 5 concertante works for solo piano... but 10.

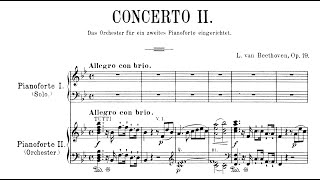

Firstly, there's the Choral Fantasy, op. 80, combining piano, orchestra and chorus in a declamation giving roots to the Ninth Symphony. The rest seem to remain away from the public eye, not even being left the dignity to possess an opus number for themselves: there's the Concerto in E-flat major, WoO 4, an early work seldom performed, the Rondo in B-flat, WoO 6, the unfinished Piano Concerto n°6 in D - which Beethoven started late in his life and never got to finish, unfortunately for the entire world - and this piece, if you dare to count it as a standalone work.

Shadowed by an insulting "61a", like a mere sputum of its original version, this transcription was written by Beethoven himself on demand of Clementi. It's actually fun to note how often the Violin Concerto has been transcribed - for cello by Robert Bockmühl, for clarinet by Pletnev, for double bass by Gary Karr... and this wide array of instrumentation isn't born from nothing: it takes its roots in the freedom which Beethoven left to the performer in his writing of the solo part, leaving much space to imagine different timbres to lead the orchestra.

Now, of course, this transcription isn't notable for any particular innovations compared to the original version for violin. Beethoven seemed not to expend much effort in his translation, leaving the orchestration intact, copying the solo part more or less note-for-note while adding a left hand in.

The two main interests are elsewhere - the first being, quite simply, the sheer difference of sound created by replacing the violin with the piano: check the differences during trills (compare 5:06 with • Itzhak Perlman – Beethoven: Violin Co... , scales (17:27 with • Itzhak Perlman – Beethoven: Violin Co... , any high-pitched passage (40:05 with • Itzhak Perlman – Beethoven: Violin Co... , and especially during the more cantabile moments - compare 26:09 with • Itzhak Perlman – Beethoven: Violin Co... both passages are of course heavenly, but in very different ways: while Perlman on the violin depicts a fragile rose in early spring, Barenboim's piano resembles drops of water on a mountain lake.

The second important thing to note are the few passages that are actually new compared to the Violin Concerto: the cadenzas. While B. didn't write any cadenza for violin in the first movement, he did write a rather special one for piano, pretty lengthy, and written with accompanying timpani (18:06 - error on screen: while Christian Tetzlaff did transcribe this cadenza from piano to violin, which you can check out at • Stage@Seven: Beethoven: Violin Concer... , it was Beethoven who wrote the original one for piano). Beethoven also wrote a cadenza for the third movement (42:15) and two lead-ins to the Rondo at the end of the second movement, of which Barenboim plays the first (33:57).

The scores for the cadenzas aren't available in the public domain, but you can find them here by Henle Verlag: https://www.henle.de/us/detail/?Title... (select "Look inside"). I couldn't include it for copyright reasons, but you can check at pages 43-51 for the first movement cadenza, pages 74-76 for the third movement cadenza, and pages 82-83 for the two lead-ins to the Rondo. (You might also want to seize the opportunity to take a look at the Preface at page 8 for more information about the creation of this piece).

0:00 I. Allegro, ma non troppo

24:11 II. Larghetto –

35:09 III. Rondo. (Allegro)

Played by the English Chamber Orchestra and Daniel Barenboim (piano and conducting).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

#piano #music #classical #ravel #chopin #liszt #beethoven #mozart #relaxing #rachmaninoff #cello #violin #lingling #cool #epic #sound #sheet #sheetmusic #pretty #beautiful #elegant #blindtest #strings #orcestra #practice #ravel #debussy #forte #mezzo #scriabin #lingling #orchestra #classicalmusic #beautifulpianomusic #solopiano #rachmaninov #pianosonata #sonata #pianoforte #chopincompetition #repertoire #pianorepertoire #pianopieces #pianomusic #synthesia #pianoconcerto #concerto

Информация по комментариям в разработке