https://benshane.com (see my work and support me)

IG: @tinkerandthink (follow for more info)

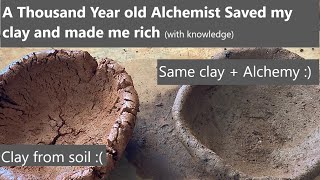

In an effort to be transparent and comprehensive and balanced, this week I’d like to show you just how bad a wild clay can be. If you go out looking for clay, you stand a solid chance of finding a good one, like the one I shared last week. But you might also find a real dud, like this one.

Trying to throw a cup with this clay required some finesse—not my forte. My first attempt ripped through it completely. By working very gently and slowly, I coerced a little cup out of this muck. I trimmed it and bisque fired it, along with a test bar.

This is a soil with a high clay content. It isn’t anything like a vein of pure clay. Some clay was deposited by the river and the clay mixed with organic matter and sand and probably manure and whatever else was around. There’s enough clay in this mud to hold it together, but barely. At the end of this video, I’ll show you what this looks like after firing in the kiln.

What makes this clay so bad? Well, it isn’t the clay itself, but rather, all the other stuff that’s in this muck that isn’t clay.

We need to differentiate a seemingly pedantic but very important pair of terms here: clay versus clay body. Almost everybody says “clay” when they are referring to a “clay body.” I do it myself, often. Sometimes it is done with full knowledge of the difference and a preference for speaking casually—usually, however, it is done without realizing what is being said or left unsaid.

Clay is a mineral. Clay is microscopic platelets that hold water between them, so that when hydrated, they slide over one another. This is what makes wet clay plastic. One clay varies from the next in the size of platelet and the precise chemical formula.

The stuff we use in pottery is not pure clay. It is a mixture of this mineral called clay plus several others ingredients. This mixture is called a clay body. Whatever you buy at the ceramics supply store is a clay body.

We add things to clay for many reasons: so we can fire it to lower temperatures, so it shrinks less, so it is less porous. For example, a traditional porcelain contains only three ingredients: kaolin (a relatively pure clay mineral) plus silica plus feldspar. The feldspar helps everything melt at a lower temperature, the silica helps form a strong and non-porous matrix, and the kaolin makes the whole mixture workable. Clay absorbs water, and shrinks as it dries and is fired to hotter temperatures. These other ingredients typically don’t absorb water, and don’t contribute to the shrinkage of a clay body.

Okay, enough of that today. That was all to get around to what’s going on with this clay—which isn’t pure clay at all. The clay isn’t the problem, it’s all the other stuff in it.

Here’s the test bar I made of this muck to measure shrinkage. A normal clay body will shrink, from wet workable clay to bisque fired, by about 10 percent. This test bar shrank only 3% from wet to bisque fired. A normal clay body might have about 50% clay in the recipe.

The somewhat reasonable conclusion to draw from this is that my little mud sample here contains about a third of the clay content as a normal clay. That is, this muck is probably less than 20% clay, and more than 80% sand, organic matter, and bugs.

And yet. and yet. It is possible to make pottery with it. So, after all, I want you to see that whatever you go out and dig, you can have some fun and experiment with it.

00:00 - Last week's video

00:29 - First attempt

01:04 - Second attempt

01:29 - Clay vs. Clay Body

03:55 - Test Bar

04:12 - Bisque-fired Cup

04:46 - Complete Failure

Информация по комментариям в разработке